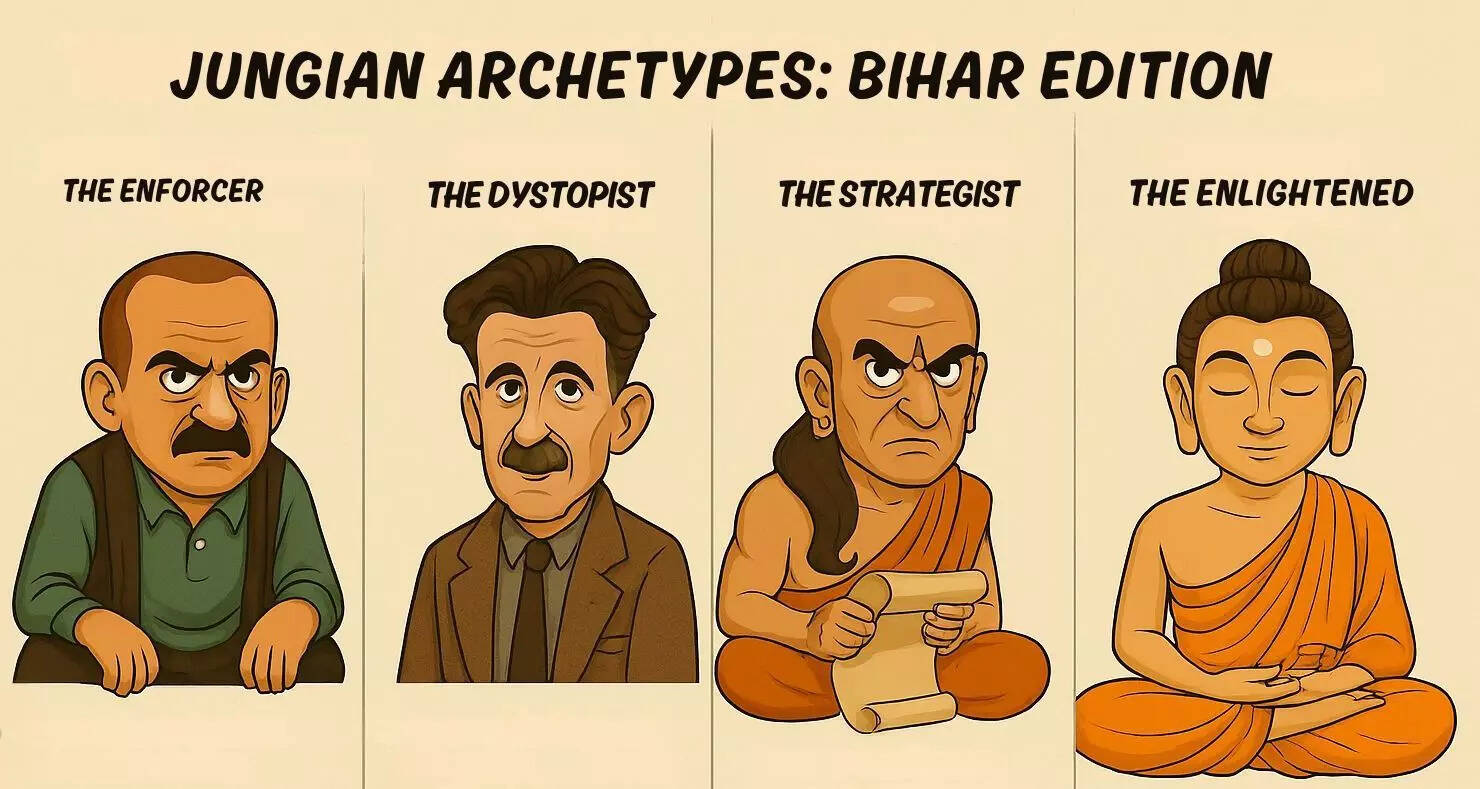

A lot of words have been written so far about why Bihar voted the way it did. Pro-regime commentators claim it’s a vindication of the current establishment’s popularity while the opposition sees the result as proof of electoral fraud or manufacturing consent by hijacking the mandate. Philistines – news channels call them psephologists – would have you believe that in Bihar people don’t cast their vote, they vote their caste, but that’s extremely reductionist thinking. The answer, as always, is deeper, and in this case the key to understanding the Bihar elections is to understand it through four quintessentially Bihari icons and their Jungian archetypes:

- Sardar Khan (The Enforcer)

- George Orwell (The Dystopian)

Chanakya (The Strategist)- Buddha (The Enlightened One)

Together, the four explain everything: how and why Bihar voted, the people complaining about the mandate, the strategist’s tryst with reality, and those that simply are beyond caring and have reached Nirvana (the state, not the 90s grunge band).

First off, we have the Enforcer AKA Sardar Khan, the protagonist brought to life by Manoj Bajpayee in Anurag Kashyap’s magnum opus, who has only one goal in life: badla (revenge). There was a time a decade ago when almost every electoral vote was for badlav, but having tried badlav in 2014, the electorate seems to be largely happy with the status quo.In Jungian terms, the Enforcer is the Shadow Animus, the primal instinct of confrontation, vengeance, rupture and settling scores, which in this case appears to be not to return Bihar to a state of anarchy.

To top it up, it was the Anima in revolt, the female voters who decided to prioritise safety and stability over tribal loyalties. There was a pre-election school of thought that many Gen Z voters wouldn’t mind voting for the MGB simply because they had forgotten or memory-holed the 90s but to borrow a phrase from George RR Martin: the North remembers.The second set to explain the post-result disenfranchisement is the Dystopist, inspired by Motihari-born lad George Orwell whose place of birth certainly influenced his lifelong desire to write bleak novels detailing fascism. From the disgruntled prince who was promised but can never deliver, to German YouTubers, to the brown-in-name-only (BINO) correspondents who cannot fathom what’s happening outside Khan Market, everyone is aghast at the result because the sanima (cinema in Ramadhir-speak) inside their head isn’t playing out in reality.

This archetype is the classic Wounded Superego which has a fundamental problem because it cannot fathom that people do not buy the same narrative as theirs, or that life under the Rand-Marx utopia of previous regimes wasn’t the social justice that was promised. Ergo, the Bihar election result is proof of institutional collapse, the state machinery being compromised, the electorate being hypnotised, and the fact that only their personal heartbreak is authentic.The third set here is the Strategist, modelled after another legend from Magadha (Chanakya). The strategist in question learnt the hard way that there’s a fundamental difference between giving gyan to the man (or woman) in the arena and being the man in the arena.

In Jungian terms, this was the Inflated Ego, the outward identity so carefully crafted (the master strategist, the election whisperer) that one begins to believe one’s own self-deception.And finally, we have the indifferent, the large swathes which have decided that no matter what happens things won’t change. After all, the regime has been in power for 20 years, and yet Biharis – white and blue collar – still have to go to other states to earn a living. Or maybe it has something to do with the state of ennui. Which brings us to the fourth archetype, named after the prince who went to the state and suddenly decided that life was simply not worth living. They are, in Jungian terms, the Transcendent Self, the archetype that rises above conflict not out of apathy but out of clarity. He has outgrown the need to win or lose, to paint saints or villains or understand mandates and narratives. He is like Sisyphus, content to push a boulder up a hill, knowing fully well that the universe will unfold as it should without any need to weigh in on it.

And together, the four of them explain everything there is to know about Bihar: the voters, the opposition, the strategist who failed, and naysayers who shall not be moved. Ergo, we have the voters who hope that tomorrow will be different, the deniers who cannot comprehend why their reality isn’t playing out, the strategist who learned that strategizing is like being a management consultant, and finally the Sisyphus stans who know nothing will change. And before one asks: Is this all just happening inside my head? Of course it is, but to quote Dumbledore, that doesn’t mean it’s not real.