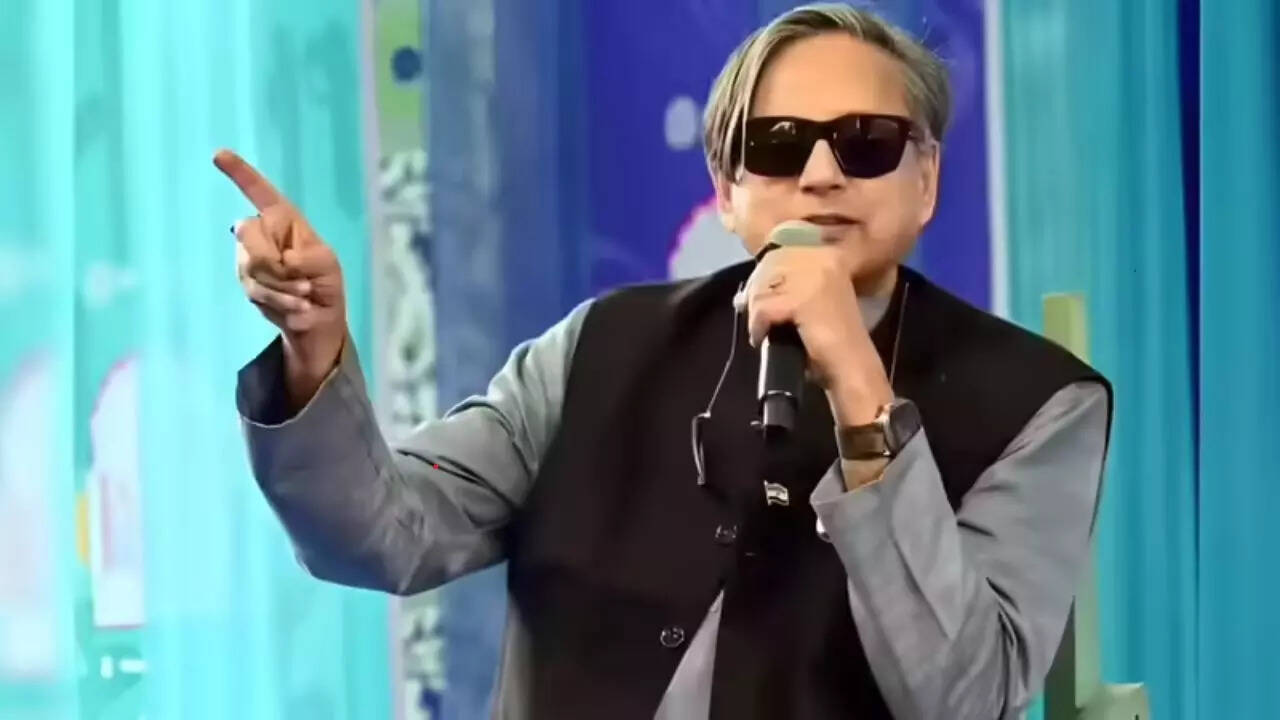

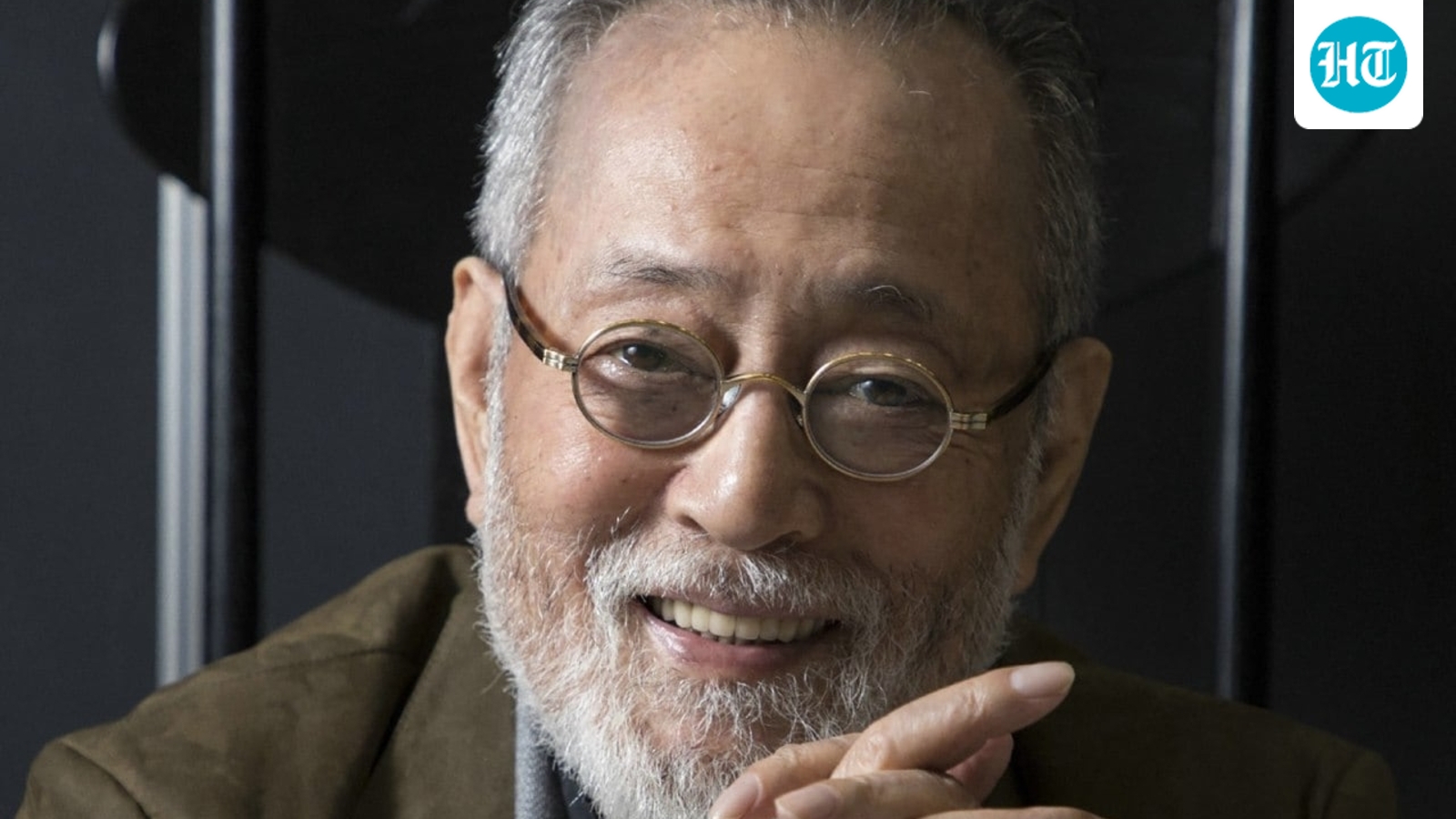

With the death of Tatsuya Nakadai at age 92 in Tokyo on Nov. 8, the world lost the last of Japan’s golden-age movie stars and one of cinema’s greatest actors. A mighty foil to the screen giant Toshiro Mifune and an often vexing suitor to a host of Japanese leading ladies, particularly Hideko Takamine, Mr. Nakadai earned his most lasting recognition in the U.S. late in his career, as the star of Akira Kurosawa’s “Ran” (1985), inspired by Shakespeare’s “King Lear.” It was a role he seemed destined to play, even if he won it more or less by default.

His connection with Kurosawa began when he served as a memorable extra in the arthouse classic “Seven Samurai” (1954), after which Kurosawa—who admired Mr. Nakadai’s swagger, along with his chiseled features and height—chose him to play Mifune’s most potent rival in the international hit “Yojimbo” (1961), which was followed by a putative sequel, “Sanjuro” (1962), in which Mr. Nakadai again ran afoul of Mifune’s ragtag hero.

The following year brought another Kurosawa pairing of the two actors, this time shorn of historical garb in favor of a modern police procedural, “High and Low” (1963), based on an Ed McBain novel. Mr. Nakadai played the dogged cop assisting Mifune’s gruff industrialist in foiling a kidnapper’s plot.

Yet it was Kurosawa’s momentous break with Mifune following the filming of “Red Beard” in the mid-1960s that later led to Mr. Nakadai being offered leading roles by the great director. The first was “Kagemusha” (1980), in which he impressively plays both a samurai warlord and the ne’er-do-well hired as his double. But when the great man dies unexpectedly, the imposter is forced to impersonate him in full. The picture won the Palme d’Or at that year’s Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for two Oscars, so drafting Mr. Nakadai for the role of Lord Hidetora in “Ran” wasn’t much of a gamble. That film proved a notable critical success on release and remains a career milestone for both director and leading man.

Though widely regarded as handsome, particularly early in his career, Mr. Nakadai’s most memorable physical feature—as he himself acknowledged—were his large, protruding eyes. They lent him a tender vulnerability in roles like that of the bar manager, opposite Takamine, in Mikio Naruse’s masterpiece “When a Woman Ascends the Stairs” (1960). But they also helped him convey a menacing intensity in more confrontational roles, such as Mifune’s reluctant adversary in Masaki Kobayashi’s too-little-known “Samurai Rebellion” (1967) and, perhaps most memorably, in “The Sword of Doom” (1966), Kihachi Okamoto’s disturbing study of a seemingly soulless 19th-century samurai. This performance, one especially dear to Mr. Nakadai, still haunts, at once repelling viewers while somehow eliciting their sympathy.

His renown outside Japan may have been secured through his projects with Kurosawa, but the films in which he was directed by Kobayashi, 11 in total, cemented Mr. Nakadai’s fame in his homeland. Kobayashi gave him his big break when he cast him as the lead in his lengthy trilogy “The Human Condition” (1959-61). The 9 1/2-hour epic is among Japan’s fiercest anti-imperialist indictments, and Mr. Nakadai’s disarmingly humane performance is central to its effectiveness.

But it’s “Harakiri” (1962), another Kobayashi film, that is considered the pinnacle of their association. The picture fuses interlocked storylines and blunt social commentary. Mr. Nakadai is narrator and protagonist, and his lean, immaculate performance complements the movie’s remarkable, spare mise-en-scène.

Mr. Nakadai continued to act steadily in film (as well as on stage in Japan) long after “Ran”; his final credit came in 2020. But no role subsequent to that of Kurosawa’s proud and foolish nobleman who descends into madness returned him to the international spotlight.

With the continued growth of streaming, the actor’s reputation seems secure and even likely to grow. Much of his best work can be seen on the Criterion Channel, which has just curated a wide-ranging tribute in his honor. But for connoisseurs of Japanese cinema, wherever they may live, his work will always be both unforgettable and essential.

Mr. Mermelstein, the Journal’s classical music critic, also writes on film.