A few days ago, Canadian director Roshan Sethi’s 2024 directorial venture, A Nice Indian Boy was released in India as A Nice Boy. The distributor reportedly cited “censorship” for the name change. The film, however, leaves no stone unturned to showcase all the mainstream cultural markers of Indian identity in the South Asian diaspora: the “nice boy” Jay (Jonathan Groff) is adopted by an Indian family and grows up steeped in Indian culture; his love interest, Naveen (Karan Soni), must navigate his partner around unsuspecting parents. They meet in a temple and aspire to a big, fat traditional wedding.

The removal of the word “Indian” before “boy” is telling because non heteronormative masculinity continues to be a cultural flashpoint even six years after decriminalisation. While the film reflects how cultural anxieties shape queer masculinity in diaspora contexts, these tensions echo a much older story of Indian cinema’s representation of masculinity and male desire.

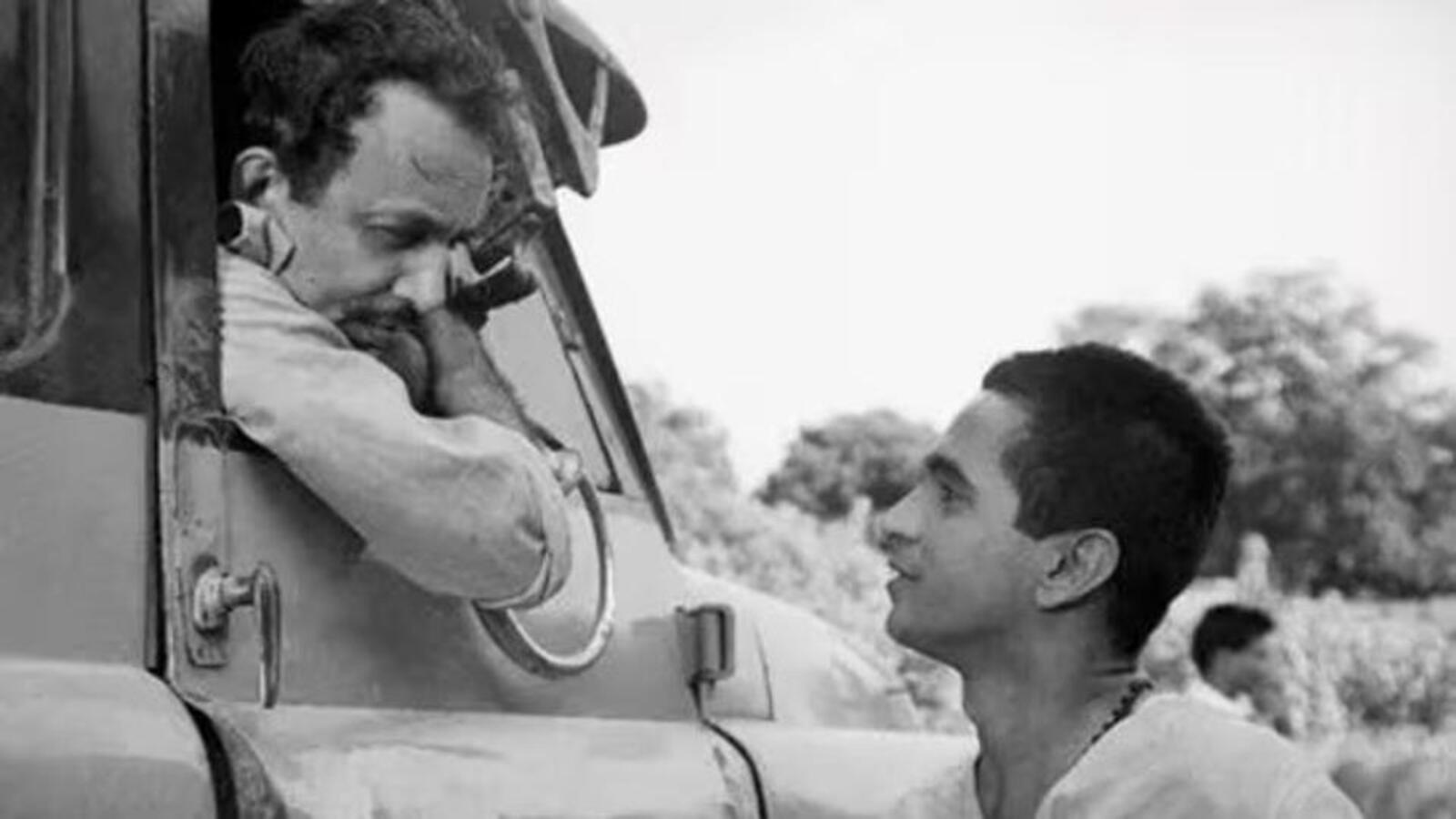

As far back as 1972, Prem Kapoor’s Badnaam Basti showed the bond between truck driver, Sarnam, and temple attendant, Shivraj. It was never declared but it was unmistakably felt, surfacing in glances, gestures, and murmured lines, reminding us that intimacy between men was never alien to an Indian masculinity rooted in the vernacular, even if the film couldn’t sanctify the relationship or do more than hint to it. Just making male for male desire visible was radical for its time.

More recently, Rohan Kanawade’s deeply affecting Sabar Bonda, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival, also depicted desire in the vernacular idiom. And while it depicted rural queer masculinity as sharing the same impulses as its urban counterpart, it was able to make the case that such desire was rendered more precarious due to its invisibility.

Between the two films, separated by a gap of over 50 years, one thing holds: queer masculinity in Indian cinema has never been only about identity but about how men learn to live within, and sometimes disrupt, the script of masculinity imposed on them. If the earliest films coded desire into subtext, and the early-2000s demanded self-definition, these newest ones achieve something quieter by letting men settle into their own love-language.

Sabar Bonda opens in the slow, deliberate rhythm of homecoming as Mumbai-based Anand (Bhushaan Manoj) returns to his ancestral village for his father’s last rites. What unfolds there is as much about the rekindling of his bond with Balya (Suraaj Suman), his boyhood friend, as it is about grief. The actors disarmingly let this tenderness emerge naturally, mutually acknowledged between the men.

Balya’s furtive rendezvous with local men stands in contrast to the emotional depth he discovers with Anand. But, around them, patriarchy presses hard with the spectre of marriage and the scrutiny of relatives. Underlying Sabar Bonda is a social anxiety surrounding unmarried men, who are not rebels or outcasts but simply illegible to a world where masculinity must be evidenced by virility. In one scene, Anand’s cousin tellingly remarks that if he has a problem, implying impotency, a doctor might help.

If Sabar Bonda lingers briefly on this unease, Anmol Sidhu’s Jaggi (2021), set in rural Punjab, pushes it to its violent extreme. Here, the eponymous young man’s suspected impotency marks him as queer, not as self-affirming identity but as an accusation rendering him an object of ridicule and unrelenting assault. This film reveals the full extent of rural bigotry. Jaggi’s vulnerability, searingly portrayed by Ramnish Chaudhary, makes him available as a body exploited without consequence.

Both these recent films emerge from a social order in which masculinity is policed and queerness must be hidden, but they approach it from opposite ends. Yet others, in contrast, imagine what it means for queer desire to step into visibility. Onir’s We Are Faheem & Karun (2024) is an intimate counterpoint: filmed in the Gurez Valley of Kashmir, it follows Karun, a security officer, and Faheem, a local, whose quiet affection unfolds with the innocence of first love. There is an unexpected openness in the remote outpost where it plays out, shadowed only by faint echoes of homophobia. Featuring Mir Tawseef and Akash Menon, the film is held together by the actors’ subtle restraint, in speech and gaze. In both Sabar Bonda and We Are… queerness no longer asks to be explained; it simply claims tenderness as its right. Kanawade shows that queerness itself contains the need to feel, be seen and chosen without apology.

This recent cluster of films sits within a longer history of visibility. Earlier attempts include Onir’s My Brother… Nikhil (2005) and Sudhanshu Saria’s Loev (2015). The former dignified the figure of the embittered gay man; the latter delivered intimacy with rare derring-do. Mainstream forays like Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020) and Badhaai Do (2022) gave us a diversity of gay leading men, albeit all straight-coded, that is, written and performed in ways that align with what was once seen as heterosexual norms of maleness. Across these films, conventional masculinity becomes the vehicle for acceptability. The exceptions only prove the rule. In Loev, Siddharth Menon is allowed a refreshing touch of flair and fluidity albeit in a supporting turn. In Rosshan Andrrews’ Mumbai Police (2013), a love interest is granted a gender non-conformity that isn’t played for laughs, but the hyper-masculine hero (Prithviraj Sukumaran) literally forgets his own desire in an improbable bout of amnesia.

These works don’t emerge in isolation, they carry traces of an older lineage. To understand how far that visibility had to travel, one must return to Riyad Wadia’s Bomgay (1996), when queerness was finally spoken aloud, and Kaizad Gustad’s Bombay Boys (1998) which, for all its trappings of class, gave a tantalising glimpse of a subculture waiting to take over. These films spoke with confidence, without seeking approval, unlike later works that aimed for acceptance.

This is not an accident. The 1990s saw the emergence of a thriving LGBT movement, led by trans people, gay men and lesbian women, for whom the politics of visibility was central. Liberalisation and later, the internet, spread ideas across a diaspora already exposed to the Human Rights discourse.

By the early 2000s, as gender and sexuality entered vernacular media and legal battles began against a colonial-era law criminalising homosexuality, India was no longer a place where sexual desire needed to stay invisible, as Badnaam Basti had suggested.

But there is still a way to go. Two years ago, the top court rejected a batch of queer petitioners who sought marriage equality. It seems that for now, films like A Nice Boy remind us that both on screen and off, the negotiation of queer desire and masculinity in India will remain contested.

Vikram Phukan is a theatre practitioner. He is working on a book on the depictions of queerness in Indian cinema from its inception.